|

|

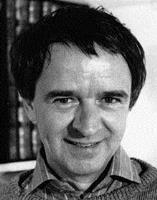

Guy ROBERT- (1933-2000) Writer, historian and art critic, doctor of Aesthetics (University of Paris)

|

''The founder of the museum of Contemporary art of Montreal, admirably described Carsonism '',

Publication Iconia,

A new ism... Carsonism,

By Guy robert

1- “I put everything I love best into my painting, and it’s just too bad for the details, they have to work themselves out. – A painting isn’t thought out or fixed in advance. As we are creating it, so it follows the mobility of our thoughts. And when finished, it is still capable of change, depending on the state of the individual viewer. –Thus does a painting live its own life, as if truly alive, only living through the one who is viewing it at a particular moment.” Picasso, 1935

“Feasting the eyes”

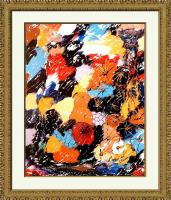

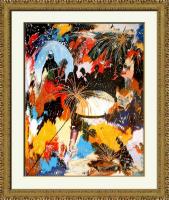

To paint is not to copy, nor to reproduce. To paint is to be evocative like Cézanne or to celebrate like Rubens. But to paint is above all to reveal, to unveil as it were, ‘donne à voir’ or to provide a feast for the eyes, as stated in the fine title of a collection of poems by Éluard published in 1939. And confronted with this painting, we are seeking just such an apparition, we are seeking to make a discovery, we are responding to this invitation to “see,” to look beyond appearances and styles, beyond cultures and epochs, to see the work in its own right as revealed by our own imaginations, which welcomes and is nourished by it, and rejoices. Let’s look at this a little in the work of Charles Carson, who accords a central place to Nature.

|

|

|

Style: Carsonism, Title: Softness 20 X 16 Circa 1993

|

- Nature is like a dictionary.

“Nature is nothing if not a dictionary,” as Delacroix was fond of saying, at least according to what Baudelaire wrote during his 1859 Salon. This celebrated poet, who was the best critic of his times, went on to establish a radical distinction between imaginative artists, who find within this so-called dictionary “those elements that accord with their own ideas of Nature and who give them a completely new physiognomy,” – and those artists without imagination who simply “copy from the dictionary” and thus fall into the “vice of banality.” By looking at reproductions of Carson’s work, you know at once that he understands how to use this dictionary of Nature with inspiration and originality.

The Earth in jeopardy

Many people look at Nature with indifference, as a space without life or interest that one goes through as quickly as possible or flees from altogether. Still others fail to see it at all. Yet when you think about it, we are all tightly linked to Nature, which constitutes the vital tissue of our planet Earth, that certain galactic observers might already be calling Pollutio, due to our lack of concern coupled with the poor treatment we have been dishing out to it, especially over the last hundred years. We have no doubt made some ecological progress, but Nature nevertheless remains ravaged and maltreated - and there are many who feel this strongly, like Carson the artist, and who take up its defence by celebrating it, each in his own way, in works of art.

Nature: to each his own…

Those who are sensitive to Nature know how to savour its generous benefits by admiring its inexhaustible marvels, respecting its unfathomable mysteries – about which science is widening the horizon, as it penetrates and analyzes its different parts. Some prefer sunsets or dawns, others are attracted by the sea or the mountains, still others find their interest more in flora and fauna or are fascinated by fossil remains below or the clouds above, by stars in starlight or the incredible spectacle contained in the mineral specimens that abound on Earth. And throughout life, each person can take different paths leading to the discovery and exploration of Nature. For Charles Carson, painting is his way of celebrating.

|

|

|

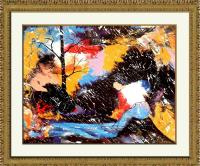

Style: Carsonism, Title: Journée ensoleillé, 20 X 16 Circa 1990

|

Signs of the inexhaustible

Baudelaire put it so masterfully in his celebrated sonnet in Correspondances: Nature makes signs to man inviting him to penetrate into its “forests of symbols” where “the perfumes, colours and sounds all echo one another.” Each of us perceives these signs in his own way, and indeed it differs depending on the company or the circumstances, the age, the point in time, the seasons and the place, the state of one’s soul. And in particular an artist like Carson, who is nourished by it, receives succour which he then transforms in the distillery of his imagination into the emotions, intuitions and visions with which he constructs his art.

Abstract art – the misunderstanding

A very large part of the art of our century seems to have moved away from Nature, turning its back on it and preferring paths toward the abstract. In that, there is a misunderstanding, which exaggerates the importance and alters the direction of this vast movement, of which the fashion has, by the way, become rather tired and top-heavy due to various abuses. We forget, for example, that the plastic evolution of a Mondrian relies on the schematization of a tree… That the magnificent gestures of a Jackson Pollock evoke mere nebulous spirals… And that Riopelle rejected the banner of the abstract artist and stood behind that of the landscapist instead – of course it was different from anything done by Ruysdael or Suzor-Côté!

His own view of reality

What was it he was offering, Riopelle, in his mosaic works from the 1950s, if not a personal and enthusiastic vision of his trips into the forest or onto the glaciers, or from his hunting and fishing expeditions? Nature is vibrant throughout his work and some time later, from about 1968 onward, a sort of bestiary quite naturally emerged, soon to be dominated by the image of the owl. The development of Charles Carson can be distinguished from that of a Riopelle in the way it moves about the frontier between the abstract and the figurative, in the common field where both styles meet. Thus is the vain quarrel that so often puts them both into opposing camps avoided, or rather the two creeds are reconciled, as the paintings reproduced at the end of these pages demonstrate by offering us their own “reality,” that of the artist’s personal vision.

|

|

|

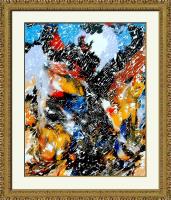

Style: Carsonism, Title: Chasse et pêche, Circa 1992

|

An admonition from Leonardo de Vinci

Reality completely surpasses all appearances, and what we perceive of it is strictly limited by our senses and our imagination. That is without doubt why Leonardo de Vinci always advised the apprentice painter to properly observe even the seemingly trivial things like an old crumbling wall or the old stones. For him, mountains and rivers might be discovered in them as well as faces and all sorts of odd scenes, in fact any sort of incredible form you like. Charles Carson has replaced the old stones by very colourful compositions with an abstract look and which are already offering us new ways of reading art: profiles of trees or of people, quick sketches of the heads of birds or fish - in short, painting which is Nature’s accomplice and which invites the use of our imagination.

Why another –ism?

No other century has gone through as many upheavals and movements as ours, in every domain- social, political, economic, scientific and aesthetic.

Why, then, add a new –ism to this already overwhelming cacophony, this deafening labyrinth?

This new “ism”? is very particular way of form pictorial writing exclusive of Carson and that we are calling Carsonism, has the particularity of being concerned with only one individual, for Carson is a rather solitary, discreet and reticent being, and would probably resist the idea of gathering a following.

- Nature and abstraction as accomplices

In the preceding pages, we have emphasized certain elements in Carson’s work: to use Éluard’s expression, Carson “lets us see,” by slipping echoes gleaned from the vast dictionary of Nature into the quivering, vibrant texture of his canvases.

At first glance, his painting has an abstract look, then signs immediately appear, traced out by the artist’s discreet hand, following his own, original approach, which forms the foundation of his aesthetic and places it on the fascinating borderline of a visual reality that makes nature and abstraction accomplices.

|

|

|

Style: Carsonism, Title: Le cirque de Shangai, Circa 1992

|

Spontaneity and energy

Charles Carson paints in complete spontaneity, carried along and inspired by the joy of juggling with forms and colours. To preserve his impetuousness, he prefers to use acrylic and spatula, rather than creamy oil pigments, which encourage the languorous brush to indulge in retouches and second thoughts.

Using the blade to cut right into the paint, he flings onto the blank canvas the quick, vigorous dance of his hand, in touches that are most often spread along the diagonal or in a broad ellipse. A feeling of freshness, of energy, of rhythm immediately emanates: freshness and liveliness of the palette, energy and variety of the compositions, rhythm that enlivens and gives substance to his visual language.

An escape from the surrounding gloom

Looking at , the freshness, energy and rhythm of Carson’s works, we might think of the best jazz, where the sense of improvisation expands the structure of the melody beautifully and innervates it with its syncopated syntax. We might also be reminded of the sonatas of Scarlatti or the concertos of Vivaldi, whose variations and modulations fuse both the overall order and the intricate subtleties of the work.

In the ware of gloom we are living through, discovering painting like Carson’s can only stimulate the stirrings and perfumes of a long-awaited spring.

A play of the eye

Carson’s pictorial language proposes a king of play of the eye, by luring it and intriguing it with ambiguous forms, which lend themselves to various interpretations following the whim of associations and the liveliness of the imagination.

Over the course of variable assemblages of shapes and colours in each painting, birds and fish thus appear, or else flowers and fruit, sky and ocean depths, trees and caverns – sometimes with human profiles, as in the amazing Shanghai Circus, in which enigmatic silhouettes keep company with bicycling-riding acrobats who slip in among specters of dragons and other festive whirls. We sense the magic and mystery of the East, with its voluptuous perfumes.

Harmonious energy

The impression of freshness and energy that radiates from Carson’s painting comes, in part, from the sparkle and purity of the colours, harmonized in their rhythmic juxtaposition and lightened by breaks of white.

The generally diagonal or elliptical arrangement of the elongated dabs of paint seems to arise from a mysterious inspiration, doubtless discreet but effective, that gives life to the composition.

It is also fascinating to see how the painting, without resorting to the artifices of perspective, creates an original depth by giving the illusion of a continual quivering on the surface, of a curve of the visual space, and of a mobility of the planes by the energetic yet harmonious arrangement of masses.

“A feast for the eye”

And so the painting once again becomes “a feast for the eye,” according to Delacroix’s ideal, and sustains interest through the game it suggests of seeking new associations of motifs, different echoes, and new flavors

Carson’s painting invites the imagination to slide along the velvety smoothness of reverie, following the signs that encourage an exploration, different for every viewer, or even for the same person from one day to the next – as Picasso suggested, in the words quoted at the start of this book.

Indeed, have you noticed, in the painting called Hunting and Fishing and reproduced opposite, the head of a deer, enhanced and topped with a plume, outlined in black against a background of ocean depths, another, while retaining a trembling mobility.

The Four Seasons

This introduction to Carson’s work could have been organized altogether differently, for example ; by classifying and analyzing the motifs in his paintings. That way, there would have been a large chapter on ocean depths and fish, other chapters on trees and bird, human figures, flowers and fruits, etc.

We will conclude it with the group called The Four Seasons, reproduced on the following pages. I threw out the idea to the artist, and he kindly accepted the suggestion, despite his reticence towards inducements or commissions.

The challenge was nevertheless remarkably well met, confirming the painter’s command of his art and the originality of his style.

Writer, historian and art critic, doctor of Aesthetics (University of Paris), teacher and conference speaker, art consultant and publisher.

Guy ROBERT has published over sixty books and a large number of articles. He has taught in several colleges and universities, and has participated in radio and television programs as well as a number of films. A well-known figure in the cultural community in Quebec, he founded the Montreal Museum of Contemporary Art in 1964, he organized the International Exhibition of Modern Sculpture at Expo 67, and other events like the M.-A. Fortin retrospective at the Musée du Québec in 1976. He has published works on art, as well as poetry and livres d'artistes illustrated with original engravings. Among his best-known works are studies of Riopelle, Pellan, Borduas, Dallaire, Fortin, Lemieux, Dumouchel and Bonet; essays on the Montreal School, l'Art au Québec depuis 1940, la Peinture au Québec depuis ses origines, l'Art actuel au Québec; and essays on Quebec literature. In aesthetics: Connaissance nouvelle de l'art, Le su et le tu, Art et non finito. He was a member of the Commission on Federal Cultural Policy in 1979-82, of the Canadian Commission of Cultural Works and he has been a recipient of the Grand Prix littéraire de Montréal.

|

|

|